BEN REBBECK, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Poor retail voter turnout is often accepted as ‘the norm’ and put down to reasons such as lack of retail investor interest to lack of company engagement. While these factors may partly contribute to poor retail voting, there is one structural cause that is relatively unknown and therefore not addressed by companies, investors or regulators.

To understand the structural impediments to voting it’s worth first reflecting on who retail shareholders are and how they came to own shares.

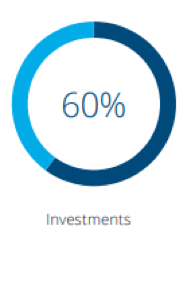

According to a 2017 ASX/Deloitte Access Economics study¹ approximately 37% of Australian adults, or 6.9 million people, hold investments that are available through a financial exchange. And around 60% of all investors use some form of professional advice (financial planner, full-service stockbroker, accountant, and/or lawyer) to help them make investment decisions.

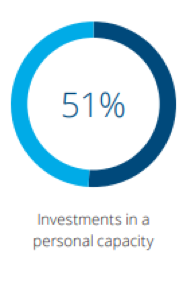

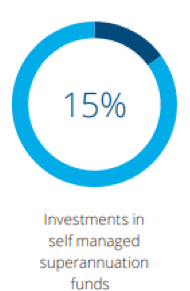

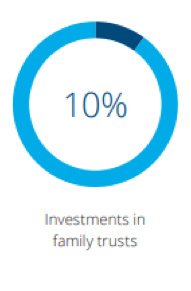

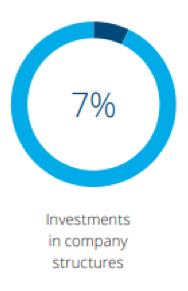

Advised investment by holding structure (Source: Deloitte Access Economics)

A recent analysis by FIRST Advisers’ shareholder engagement team found that, contrary to expectation, it was this latter group (retail investors who use some form of professional advice) who were the laggards when it came to voting.

So what is going on here? Surely, if you are a well-advised and a relatively wealthy investor, you are going to care about your investment and vote, right?

Unfortunately, it is not as simple as retail disinterest impacting a desire to vote. There are structural problems with the way retail investor portfolios, that are not directly held, are managed and around half of all advised investment is not held directly. This means that, like Institutional Investors, the registered holder of almost 50% of all retail shares is a:

- Custodian,

- broker or platform account,

- other financial intermediary (such as an outsourced SMSF administrator),

- company, or

- some or all of the above.

While institutional shareholders have evolved mechanisms to vote through these holding structures, at the retail level, this is not the case and the financial incentives of advisers and registered holder (custodians), are not designed to facilitate retail investor voting.

On the one hand the registered holder or administrator of the shares is incentivized to focus on efficiency and minimizing cost while the financial adviser remains focused on investment returns and risk.

When this structure is applied to retail voting, the financial conflict becomes apparent. While voting is arguably a valuable right that contributes to long term wealth creation, it is neither in the custodian’s nor advisers’ immediate financial interests to facilitate their clients’ voting or to care about ESG matters. And often they both pass the buck to the other as the party responsible for facilitating voting.

But where does this passing off of responsibility take us when both custodian and adviser are part of the same financial intermediary? Surely fault cannot be laid upon the investor or company, when the investor was never made aware of a vote, nor advised how to vote.

For example, in a recent solicitation campaign, FIRST Advisers found that approximately 9.94% of the listed entity’s securities were held by retail investors and registered in the accounts of a large investment bank’s custodian. Under the custodial agreements, despite the significant and potential deciding influence of their retail clients’ votes, the custodian was not required to, and did not, send a single Proxy form or Notice of Meeting to any of their retail clients, (other than to a retail investor who was also a member of the C-suite of the company that was subject of the vote and individuals who had a holding in excess of 5% of the issued shares). Further, that custodian had no facility online or offline to enable their clients to directly participate in the vote.

In this circumstance, it was up to each retail investor to engage with their financial adviser, about a meeting they were never told about by their custodian. They then had to get their adviser to facilitate their vote, something for which the adviser received zero remuneration. After all of this, the custodian still said that they would not vote any shares for the retail clients, despite the custodian being a substantial registered holder collectively.

Needless to say, voting turnout from this large retail group was nil.

And unfortunately, this situation is not restricted to just that financial institution, or that listed entity. We see it replicated across almost all entities in the ASX All Ordinaries Index, and is the one of the major drivers of low retail voter turnout.

It could be argued that in these circumstances, financial advisers are poorly servicing their clients. However, when we see this pattern occur broadly across the market, it becomes clear there is a structural deficiency in the market itself. And it is a deficiency that retail investor intermediaries are not financially incentivized to care about, and one the regulator appears not to be aware of or not to appreciate how much it impacts investors or their investee companies.

So the lesson from this situation is two-fold.

Firstly, financial intermediaries can do a much better job at assisting their clients to vote. Buck passing helps no-one. And if there is structural reform required, perhaps now (in the Post-Hayne era) is the ideal time for the regulator to do more.

And secondly, for the listed entity, merely communicating with shareholders in the minimum fashion will likely mean you are not communicating at all with a large segment of your retail shareholder base. Starting early to better understand the composition, identity and structure of your retail shareholder base through analytics will place you in a position to bypass the structural impediments between you and your shareholders.

[1] https://www.asx.com.au/education/2017-asx-investor-study.htm